Imaging 2D Gels: Essential Tips and Tricks

Introduction

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis stands as a cornerstone in comprehensive proteomic investigations and host cell protein (HCP) antibody coverage validation. Crafting your own gels demands meticulous effort, encompassing rigorous sample preparation, optimization of electrophoretic conditions, and judicious selection of staining methodologies. After dedicating substantial time to these preparatory stages, the final task is the precise imaging of your gels, pivotal for subsequent computerized analysis.

The imaging step is at least as important for the analysis of your experiment as each of the previous experimental steps.

This guide aims to assist you in preserving the information captured within your gels, ensuring they serve as the best possible inputs for advanced 2D gel analysis software, such as our SameSpots or SpotMap software.

Always remember that the quality of your analysis is directly linked to the quality of your images, good data in = good data out.

Checklist for High Quality 2D Gel Imaging

- Grayscale Imaging: Opt for grayscale images over color to enhance clarity.

- Maximize Grayscale Spectrum: Adjust settings to utilize the full grayscale range for each dye employed.

- Optimal Resolution: Select a resolution ensuring that the smallest spots of interest possess a diameter of no less than 5 pixels.

- Consistent Orientation: Maintain uniform orientation across all gel images.

- Standardized Positioning: Place each gel identically on the imaging apparatus; if feasible, focus solely on the region of interest.

- Uniform Parameters: Apply consistent imaging parameters throughout your experiment to facilitate reproducibility. Save and reuse profiles encompassing these settings and designated regions of interest.

- Individual Dye Adjustment for Multiplexing: Tailor imaging parameters separately for each dye in multiplex experiments.

- Minimal Post-Processing: Restrict post-imaging modifications to cropping, mirroring, or rotations of 90°, 180°, or 270° (all of which our SameSpots and SpotMap software can perform)

- Dedicated Software Usage: Utilize the image processing software accompanying your imaging device. Refrain from employing third-party applications, such as Photoshop, unless fully aware of their impact on quantitative analyses.

- Appropriate File Formats: Avoid using JPEG files for quantitative purposes. Prefer calibrated formats like GEL or IMG/INF over TIFF when available (all of which our SameSpots and SpotMap software support)

Selecting the Appropriate Imaging Device

Scientific scanners and cameras are intricate instruments. Understanding their operational principles is crucial for making informed choices regarding gel imaging.

The fundamental operation involves light emission from a source, its interaction with the gel, and subsequent detection of the modified light by a sensor. The detected signal’s intensity is measured at each gel position and converted into numerical data via an analog-to-digital converter, culminating in the final image file.

Imaging Modes

- Transmission Mode: Light traverses the gel and is directly measured by a detector positioned opposite the light source.

- Reflection Mode: The gel is situated between the light source and a reflector. Light passes through the gel, reflects back, and traverses the gel again before detection.

- Fluorescence Mode: Fluorescent dyes within the gel are excited by specific wavelengths and emit light at longer wavelengths, which is then detected.

For superior data quality, transmission mode is recommended, as it minimizes saturation effects prevalent in reflection mode, where intense spots may appear overly dark due to light traversing the gel twice.

Image Resolution Considerations

During imaging, the gel is divided into a grid of pixels. Smaller pixels correspond to higher resolution, revealing finer details. However, excessively high resolution increases file size and processing time without significant gains in detail (you reach a point of diminishing returns). For image analysis of protein spots, aim for a resolution where the smallest spots of interest are represented by at least 5 pixels in diameter. As an example a very small spot of a diameter of 1mm imaged at 200 dpi will have a diameter of approximately 8 pixels.

Every doubling of image resolution causes a fourfold increase in the resulting file size. Scanning takes longer, files end up larger and therefore the analysis of those images require more system resources such as RAM and CPU power.

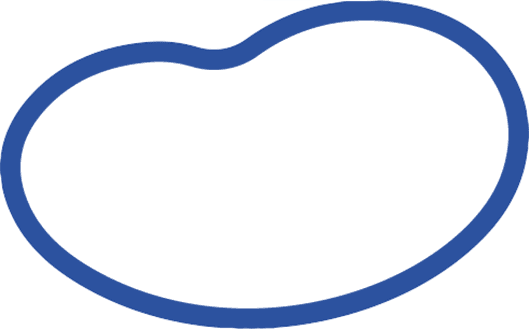

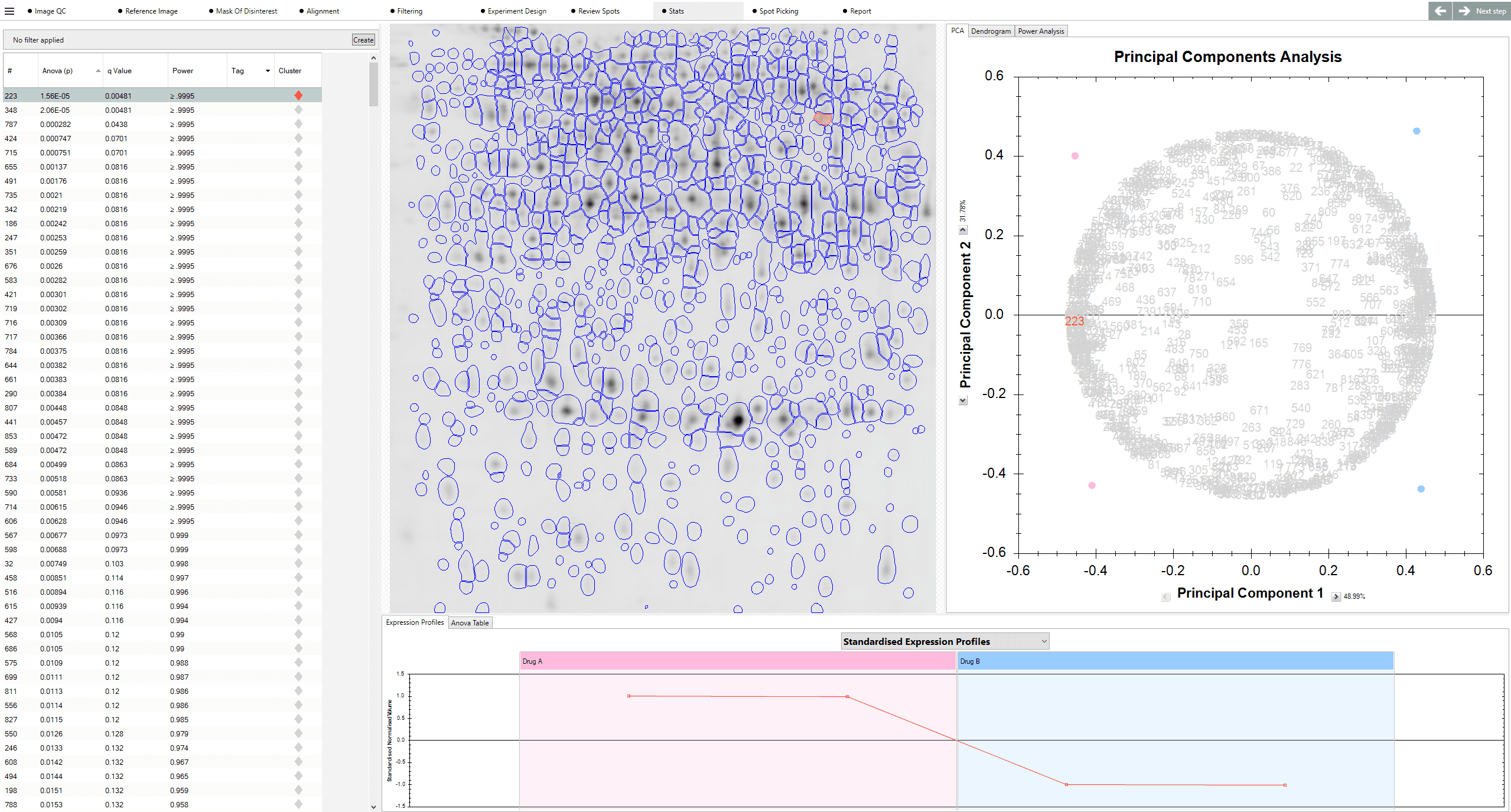

Spot detection on a 20cm 2D gel image, captured at a resolution of (a) 100dpi and (b) 300dpi. The lower resolution of the 100 dpi image is apparent by the degree of pixilation. In this image, there are fewer pixels present to represent the spots (approximately 2 orders of magnitude less pixels in the 100 dpi image compared to the 300 dpi image).

Enhancing Dynamic Range

Maximizing the distinction between signal and background pixel intensities is vital for accurate image analysis. Maximizing the distance between background and the top signal intensity in an image means to fully exploit the dynamic range of your equipment. Adjust imaging settings to cover the full dynamic range of signal intensities, ensuring subtle differences are discernible from each other. Be cautious with post-processing adjustments, as they can distort quantitative data and reduce the dynamic range of the image.

Example A: Good dynamic Range (67% of available)

Example B: Low dynamic Range (12% of available)

Figure 4. (a) An example of good dynamic range using linear and log plots of pixel histograms showing 67% of the available grayscale range in use. (b) An example of a low dynamic range using linear and log plots of pixel histograms showing 12% of the available grayscale range in use.

There are several ways to

Image Saturation

When optimizing the dynamic range, it is important to avoid saturation effects. Saturation occurs when grey levels exceed the maximum available. When a spot becomes saturated, any differences in high pixel intensities cannot be resolved, and the spot appears truncated when viewed in 3D (Figure 5).

Figure 5. (a) View of an area of saturated spots on a gel image; (b) and (c), the same area represented in 3D.

Why can saturation be a problem?

The outline-based spot detection in our SameSpots and SpotMap software packages are not optimised for the unnatural shape of these spots, since the peaks are effectively ‘missing’ in the scanned image, and no reliable quantitation can be done with them.

Recommendation

If possible, only scan the area of the gel you are interested in. Perform any cropping at the time of scanning to remove blank parts of the scanner plate, labels etc. The extra areas provide no useful information, can ‘steal’ dynamic range, distort image statistics and increase storage requirements. You can adjust the dynamic range in CCD camera systems by altering the exposure time, or in a laser based system by fine tuning the voltage of the PMT detector. It should be as high as possible across all your images, without saturating, given you should not change settings between different images in the same study. You should consult your scanner documentation, or contact your scanner supplier, for information on how to achieve this.

Image Bit Depth

Also referred to as color depth or pixel depth, bit depth is the number of bits used to represent the grayscale (intensity level) of each pixel in an image. Greater bit depth allows a greater range of shades of grey to be represented by a pixel. For example, an 8-bit grayscale image file stores 256 shades of grey for each pixel, while a 16-bit image file has 65536 possible grayscale values for each pixel. The following table indicates the possible grayscale levels available for the types of images commonly used for gel image analysis.

| Bit Depth | Intensity Levels |

|---|---|

| 8 | 256 |

| 10 | 1024 |

| 12 | 4096 |

| 16 | 65536 |

In reality, the images displayed on the computer screen will only be represented in 256 shades of grey, and so an 8-bit image will look identical to a 16-bit image by eye. However, image analysis software can distinguish between the different levels of grey.